What we can learn from Alexa’s mistakes

Conversation. The key to human-to-human interactions; a spectrum ranging from cavemen around a camp-fire, to lengthy political debates, through to awkward small talk with your dentist.

Design challenges for conversational UIs

Conversation. The key to human-to-human interactions; a spectrum ranging from cavemen around a camp-fire, to lengthy political debates, through to awkward small talk with your dentist. Something that we've really got sussed- we quickly make decisions about whether someone is interesting, not paying attention to us, if we want to date them or employ them, based on it. If we want to get something done, we talk about it - it's how we transmit information and transact between people.

So, it just makes sense that we would use conversation to interact with services and products - right?

Right. But it turns out there are some challenges about creating an artificial conversation counterpart, especially one that can access your finances or send a message to your boss. These challenges, which have long been resolved for human-to-human conversation, have yet to be fixed to the same extent in conversational interfaces.

Conversation is the interface we all know, so it is unreasonable for the interface designer to expect the user to have to re-learn it in order to interact with a service... it is on the service to understand however the user chooses to naturally converse with the system.

Here are some interface challenges, highlighted by Amazon Alexa's recent boom in popularity:

Authentication

⚡ "Who's speaking?"

In a story on a local news show, the news anchor imitated a girl who accidentally ordered a dolls-house via a conversation with Alexa... Hearing this as a command, the Alexa interface in the homes of many viewers responded by trying to order a dollhouse as well...

“I love the little girl saying ‘Alexa ordered me a dollhouse”

Authentication is essential in transactions and interactions with services: we expect reasonable safeguards — especially when paying and logging in. When dealing with our money and personal information, we need to be careful to protect it. Conversational Interfaces pose new and unique challenges here, like accidental noise interference. This just couldn’t happen accidentally on a physical touch interface — you'd have to intentionally elbow the owner out of the way just to get your paws on screen!

In human-to-human interactions, we use multiple forms of authentication without even thinking about it:

- Face to face: We recognise who we are speaking to by their appearance - after all, you know what your friends look like.

- Voice: We recognise the sound of the person we are talking to, their tone, vocabulary etc. You would probably notice if someone unexpected picked up the phone instead.

- Location/intuition: We make logical assumptions about our likelihood to run into someone that we know in a new place. Spot someone that looks familiar whilst on holiday? Well, surely it can’t be…?

But how can a chatbot verify people?

A half-way measure here is to use old-school validation methods such as a passcode, which whilst clunky, tend to work reasonably well. The ideal solution here however, is having enough info about the user's voice and appearance (depending on the medium), so that the interface can recognise the user without clunky and experience-breaking input - imagine the equivalent of your friend asking you to re-verify that you are who you say you are before lending you money for example...

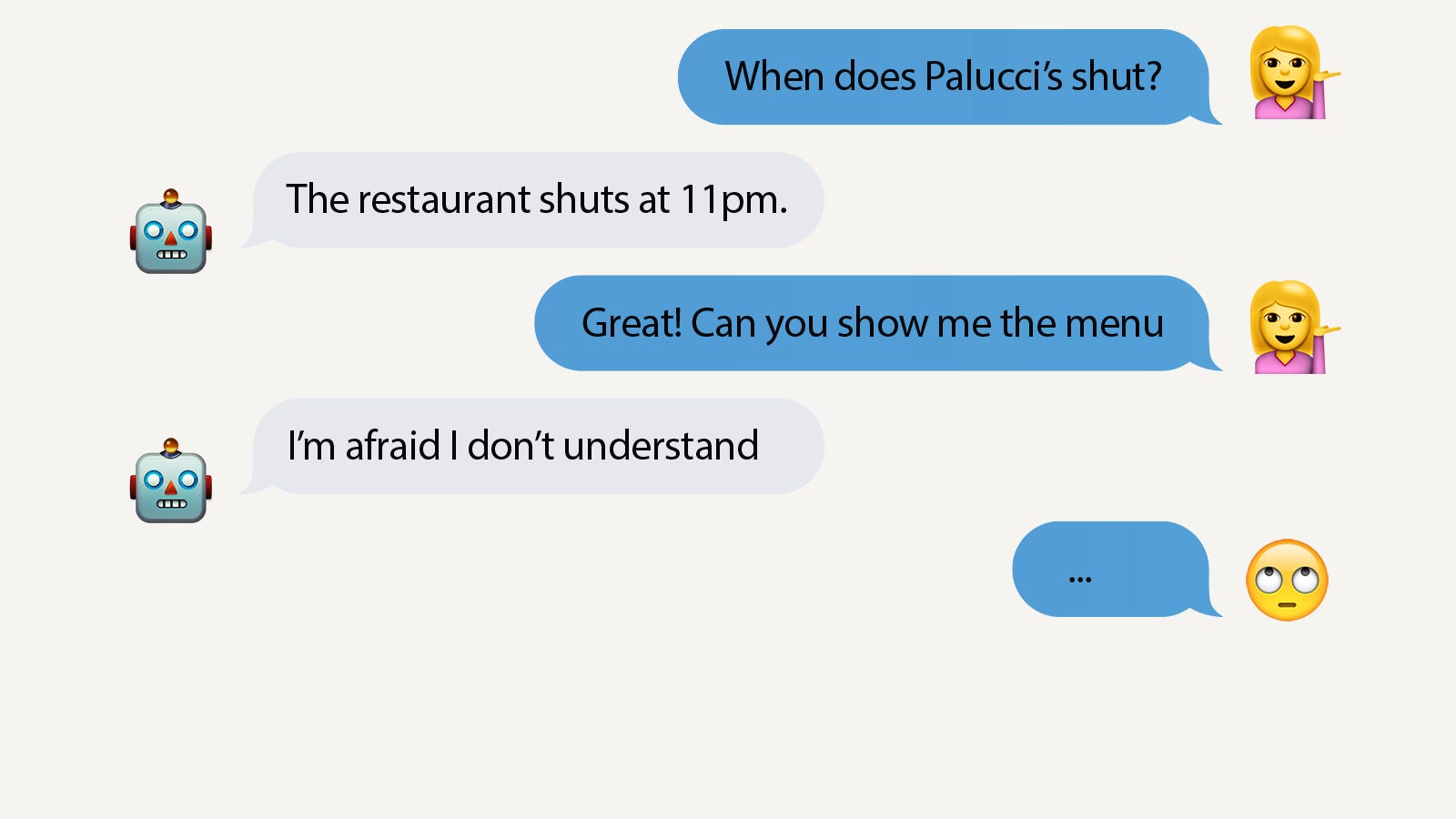

Context

⚡ "What are you talking about?"

Deeply related to that last news-story problem is context; if Alexa had recognised the context of the news programme (that it was a TV show, presenter giving an example, the use of past tense), then Alexa wouldn't have taken action.

This is something that we take for granted in human-to-human interactions - that the other party can remember where we are, what we are doing, everything we've just spoken about. After all, you probably wouldn't spend too much time with a friend that couldn’t remember the last thing you said.

The need for contextual understanding runs deep - from Alexa knowing when to stay quiet, through to knowing that a question may relate to something previous (as in normal conversation), or what version of a homophone the user is saying (whether you are hungry or going to Hungary).

The real challenge here is that it is almost a zero-sum game; you either have rich contextual info defining the Conversational Agent's behaviour, or nearly none at all - because if even slightly inaccurate, it could make the Agent either unreliable (wrong understanding) or unresponsive (taking the wrong action from its understanding). Of course, as platforms such as Alexa learn more abilities, they become smarter and more useful.

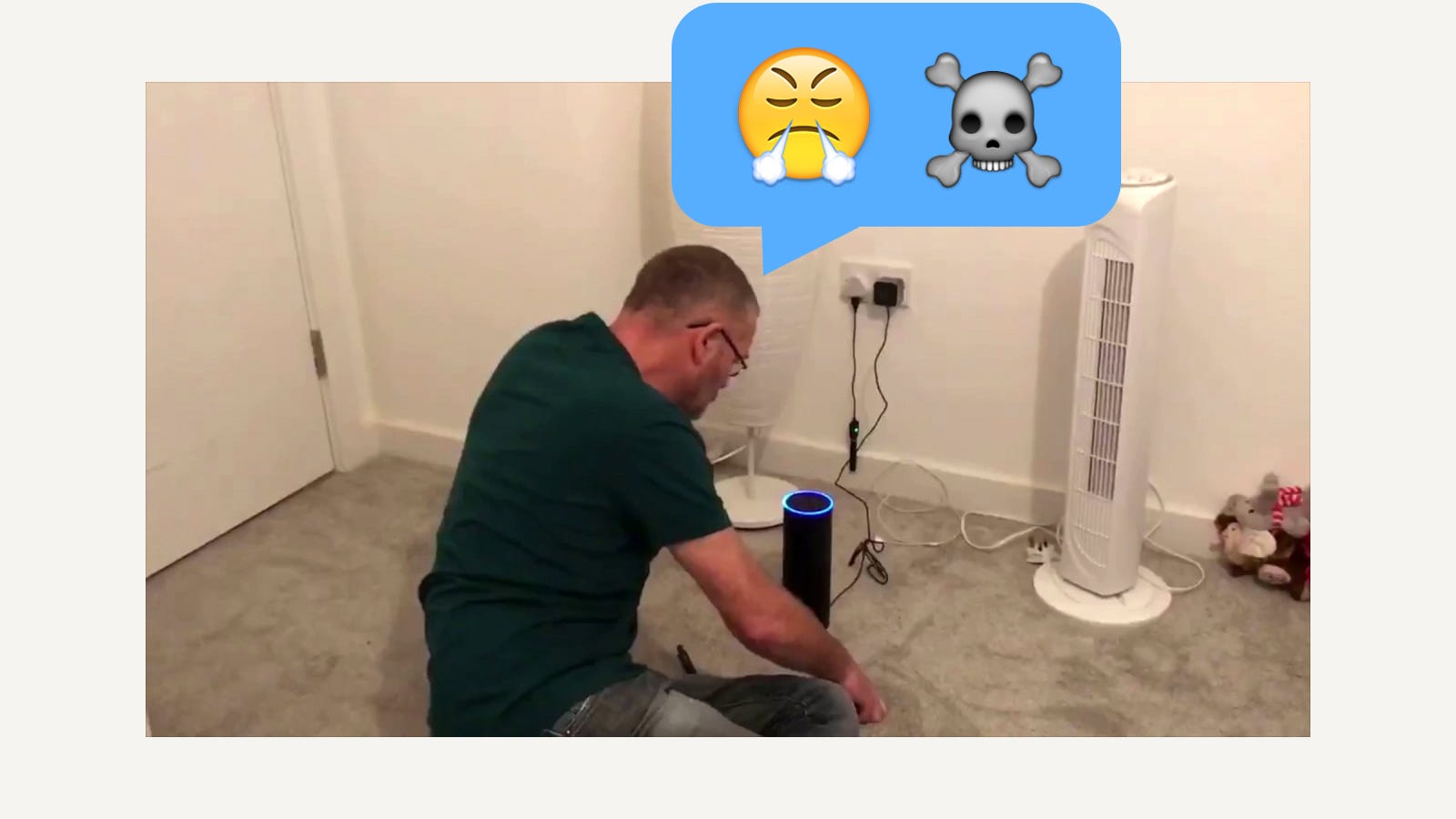

Awareness of user

⚡ "Who am I speaking to?"

In a viral video, a child asks Amazon Alexa to play his favourite song… However, Alexa misunderstands and tries to offer something quite different.

A Conversational Interface is more likely to be shared between people - much as Alexa is designed to be a presence in the home (perhaps even a digital family member), and so it needs to understand the different users and adapt to them. It should know its user’s preferences, age and the level of response to give them —and if they are a kid, then they should get a child-friendly response.

Much in the same way that people adapt their language based on who they are speaking to and their relationship with the person, a Conversational Agent should also adapt its tone and language based on its audience. This can also spill back over into context — if a user is clearly in a rush, then the service needs to adapt its tone to be more quick and direct. A Conversational Agent needs to know its audience.

Intelligence

⚡ Alexa: "Sorry, can you say again?" User: "Don't worry..."

We use conversation everyday. As a result, people have certain expectations from conversation which differ from other kinds of interaction. At the centre of it, there is an expectation of understanding — and a frustration that rises from needing to repeat yourself or being repeatedly misunderstood.

What makes a Conversational Interface exciting and novel is that it can be entirely handsfree and invisible. However, this means it HAS to work smoothly, as there are no soothing buttons to pummel, or options for the user to try.

Call and response… speak and wait.

Unlike the immediacy and feedback we have come to expect from graphic user interfaces (with haptic feedback (e.g. vibration), roll-over states and loading icons to soothe our impatience), Conversational Interfaces need time to hear the entirety of the input and know that it has concluded before it can respond — and then the user has to listen to the entire response to know if the interface actually did the right thing.

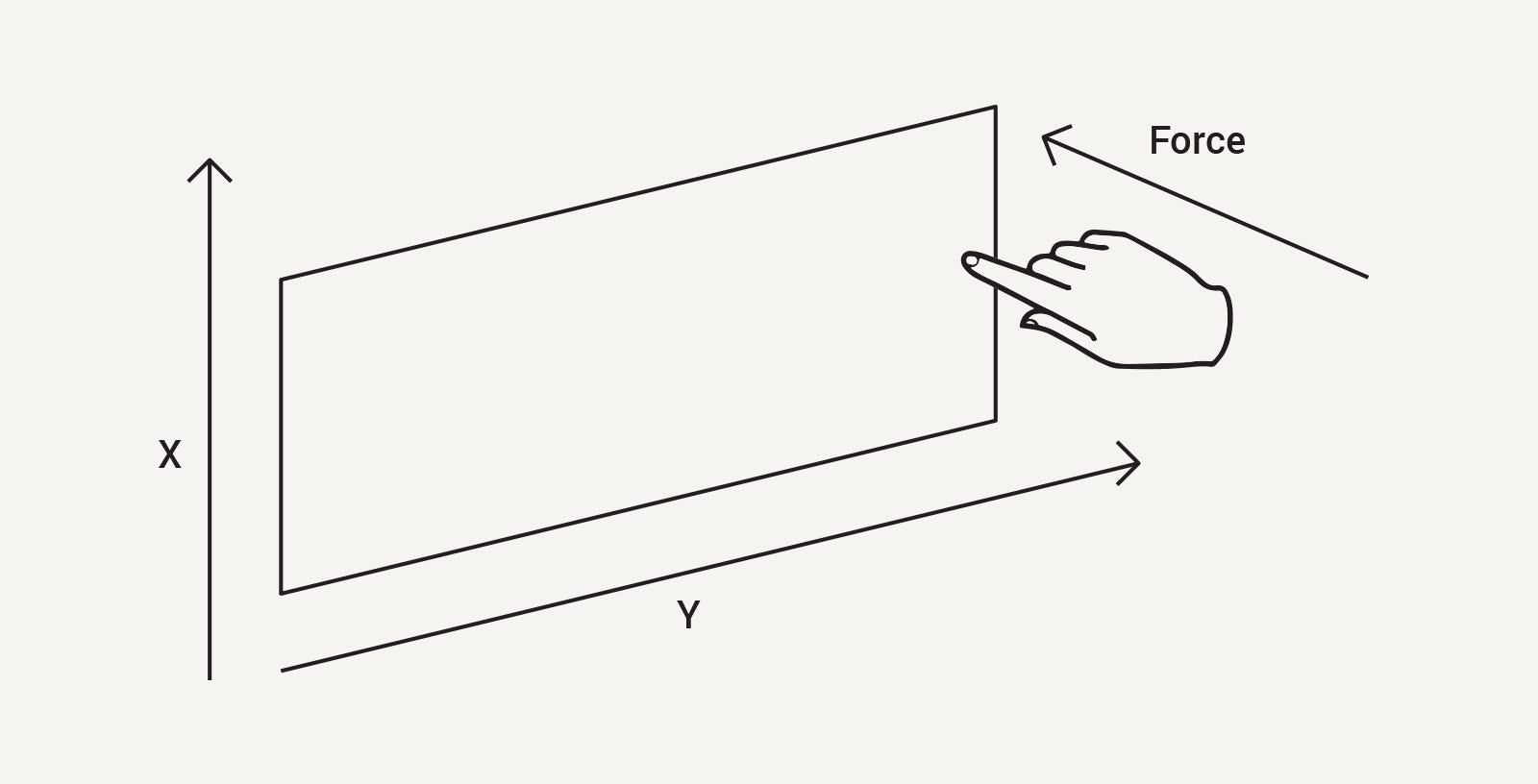

To emphasise, the inputs for a touchscreen are immediate: where the user touched and how:

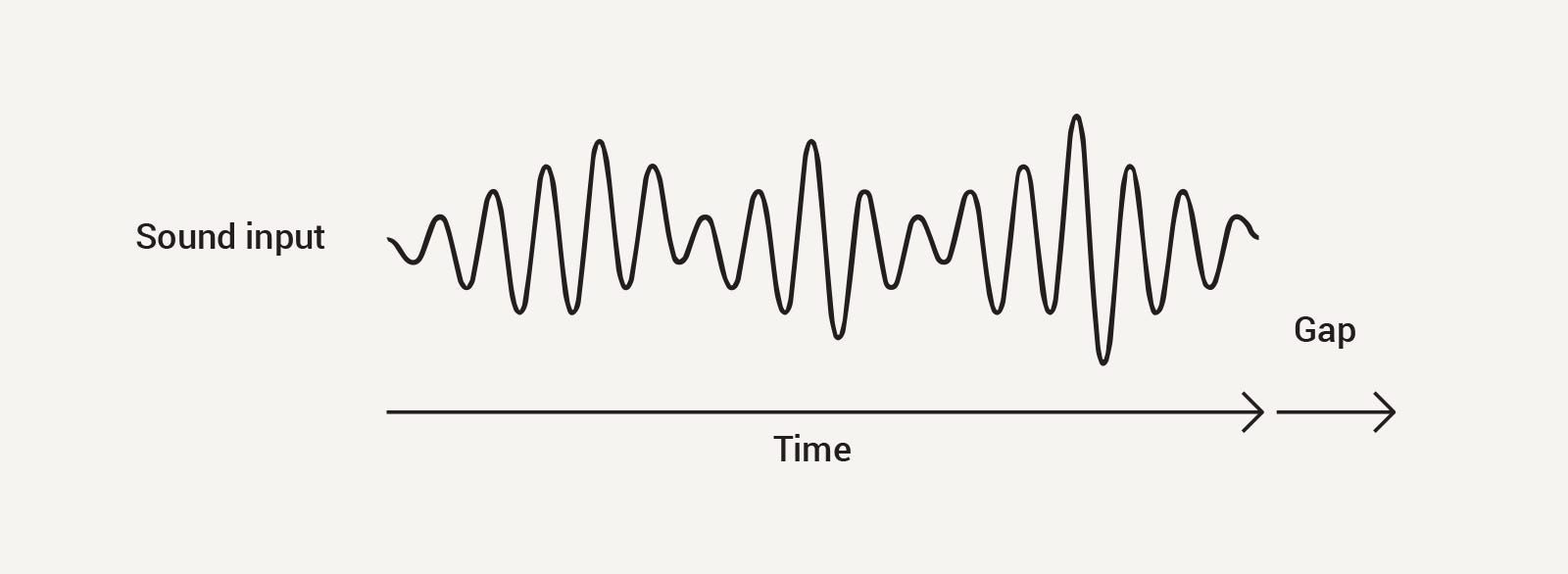

…but a voice interface’s main input is a sound wave changing over time, as shown below:

This extra time has to be factored into designing new kinds of interactions specifically for conversation — it is not enough to simply adapt existing interaction models to this new kind of platform.

Where do we go from here?

We need to learn how to create natural conversational alternatives to our existing graphic interfaces, understanding that it is a fundamentally different model to how users expect to transact with services and businesses. What is not new is conversation itself, and we must pay homage to the fact that humans have created intuitive mechanisms for person-to-person conversation which we should not expect them to relearn.

How do we do this?

Make it painless:

Humans anthropomorphise everything with a hint of life — by making smart use of data (including context, user behaviour, and user attributes), we can provide a conversational counterpart that behaves in a way that isn’t jarring, and that users can feel comfortable with.

Furthermore, people change their mind mid-sentence, or don’t always express themselves clearly and the interface needs to be able to take these noisy inputs and make a best guess at the user’s intention.

Make it trustworthy:

Auditable. An interface or agent that is invisible and acts on your behalf needs to be auditable. In order for a user to trust their finances and reputation with something that cannot be seen, it needs to be clear about the actions it takes and why it took them.

Transparent. Where the Conversational Agent can’t provide the minimum required experience, clearly communicating the limitations of the system will help users to avoid running into walls or having poor experiences.

Lastly, it is important to understand that Conversational Interfaces simply provide another way to interact, but cannot be expected to entirely replace visual and other approaches. Just as a picture says a thousand words, words are not necessarily the most effective means of achieving a goal, and we need to consider and embrace this. An ideal world of interaction likely looks more fluid: seamlessly changing between types of interface to the most appropriate for a given task.